Nicholas Kristof & Sheryl WuDunn discuss ways to address opportunity gap

Posted: October 3, 2014 Filed under: Education, General, Income Leave a comment »Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s new book “A Path Appears” looks at barriers to opportunity around the world, and what can be done to overcome them. Some of those barriers are already in place at the beginning. As WuDunn puts it, some kids are born “behind the starting line.” She says a child born in the bottom 20 percent of the economic spectrum has a one in 12.7 percent chance of making it to the top 20 percent.

WuDunn and Kristof spoke at Sacred Heart University on Friday to talk about the book. WSHU’s Craig LeMoult asked them about the gap, and how it can be addressed with early intervention.

WuDunn says by the age of four, a child of professionals has heard 30 million more words than the child of parents on welfare. That gap can make a significant difference in a child’s development.

“Part of that is an income issue,” says Kristof. “People don’t have resources for babysitter, or may send somebody to a child care program that may be inadequate. But it’s also, to some degree, cultural.”

Kristof says the gap between wealthy and poor children is increasing.

“Middle class parents have been investing more and more and more in their kids’ enrichment programs, and sending their kids to music lessons, then chess lessons, and soccer practice,” he says. “So the gap in those enrichment programs has gotten greater over the last generation, rather than smaller.”

But, Kristof says, it’s a mistake to think there’s not much that we can do to narrow that gap. Here’s what they had to say about early interventions that can make a difference:

“There are very very few people who don’t want the best for their kids,” says Kristof. “And where there are shortcomings, they may be raising their child the way they were raised. And if they get some support, some parental coaching, some help – especially with the incredibly difficult job of being a single parent – then they can dramatically improve those outcomes.”

In particular, Kristof and WuDunn point to the effectiveness of the Nurse Family Partnership, which provides coaching to new parents, even before a child is born. Teaching parents not to smoke or drink, and to breastfeed and hug a baby, can have a huge impact on a child’s development. They say families who get coaching from the Nurse Family Partnership see a 79 percent drop in state-verified child abuse, and the children are half as likely to be arrested by age of 15.

A program that’s working to close that 30 million word gap is Reach Out and Read, which provides books to low income families to help with the cognitive development of children. The program provides books, and doctors “prescribe” nightly bedtime stories to families. Here’s Kristof and WuDunn describing the program.

The cost is $20 per child per year. But Kristof says only a third of children who would benefit from the program in the U.S. get that intervention.

Kristof says unlike the U.S., economic inequality has declined globally. In particular, he says one of the great global changes has been an increase in literacy.

You can hear the full audio of Kristof and WuDunn’s discussion here.

Connecticut ranks last for school breakfasts; economics play a role

Posted: May 27, 2014 Filed under: Education, Nutrition Leave a comment » For the last eight years, Connecticut has ranked last in the nation when it comes to number of schools offering breakfast to students. In the last national report in 2012, less than half of students who received free and reduced lunches in Connecticut ate breakfast at school. There’s a clear economic divide between the schools where breakfast is offered and where it isn’t. The state’s larger, lower-income cities generally offer it, and many of the smaller, wealthier communities do not. Here’s Craig LeMoult’s story about school breakfasts in Connecticut:

For the last eight years, Connecticut has ranked last in the nation when it comes to number of schools offering breakfast to students. In the last national report in 2012, less than half of students who received free and reduced lunches in Connecticut ate breakfast at school. There’s a clear economic divide between the schools where breakfast is offered and where it isn’t. The state’s larger, lower-income cities generally offer it, and many of the smaller, wealthier communities do not. Here’s Craig LeMoult’s story about school breakfasts in Connecticut:

This interactive map by the Connecticut State Data Center illustrates the number of school breakfasts served in each school district, compared to the number of students receiving free or reduced-price school breakfast. Towns with more “free & reduced” kids and fewer breakfasts are red.

New Conn. high school graduation rates show continuing economic gap; some progress

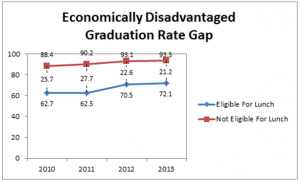

Posted: May 14, 2014 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »The Connecticut Department of Education released new statistics on Wednesday showing an improvement in the percentage of students who graduate in four years, and a slight reduction in the gap based on the economic background of students.

In 2013, 68.6 percent of students who are eligible for a free lunch (the standard way of assessing poverty in schools) graduated in four years. In 2012, that percentage was slightly lower, at about 66 percent. For those who get a reduced-price lunch in 2013, 84.2 percent graduated in four years. Compare that to the percentage for kids whose families make enough money that they don’t qualify for any lunch assistance: 93.3%.

Last year’s numbers were released in August, and were featured here in State of Disparity.

Here’s an interactive map by the Connecticut State Data Center, illustrating graduation rates in each Connecticut school district.

Since 2010, the graduation gap between economically disadvantaged students and their more affluent peers reduced by 4.5 percentage points (17.5 percent).

The DOE has set aside the 30 lowest performing school districts in a designation called “Alliance Districts” that are getting additional funding. Those districts saw a 1.3 percent increase over 2012. Of those, the 10 lowest performing saw a 2.8 percentage-point increase — from 66.3 percent in 2012 to 69.1 percent in 2013.

Four-year graduation rates by district and school are available at the following links: District, School

Of course, if a student doesn’t graduate in four years, it doesn’t necessarily mean they won’t graduate at all (as we saw in this story). So the DOE also released, for the first time, the percentage of students who graduate in five years.

Looking at all students who entered Grade 9 in September 2008 (so they ordinarily would have graduated in 2012) the five-year graduate rate is 87.5 percent – 2.7 percentage points higher than the cohort’s four-year rate. For kids who are

eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, adding that extra year brings up the graduation rate 5.3 percentage points.

Five-year cohort graduation rates by district and school are available at the following links: District, School

This graph from the Conn. Department of Education shows a continuing significant gap in graduation rates between students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, and those that don’t. Although the state points out the gap decreased from a 25.7 percentage-point difference in 2010 to a 21.2 percentage-point difference in 2013 for a total reduction of 4.5 points.

There are persistent racial gaps in grad rates, too. In 2013, about 91 percent of white students graduated in four years, while about 76 percent of black students and 70 percent of Hispanic students graduated in the same time.

Listen to Ebong Udoma’s story here:

Malloy discusses disparity and workforce training with National Governor’s Association

Posted: October 22, 2013 Filed under: Education, Income Leave a comment » At a summit of the National Governor’s Association in Stamford on Tuesday, Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy spoke with Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin and others about the economic importance of education and workforce training. You can listen to Craig LeMoult’s report here.Governor Fallin said 50 years ago, 80 percent of middle class jobs in the country required just a high school degree or less. “Today that number is 35 percent of our jobs require a high school degree or less, and two thirds of those jobs will pay less than $25,000 a year,” said Fallon.

Malloy said there’s no reason to believe Connecticut is not leading the country in the decline in the number of jobs available to people without a higher education degree. “And then, in some of our urban areas, we have a larger than we should find acceptable numbers of students that don’t even get the high school degree, at least in the standard 13 years,” said Malloy. “So this is a big questions for all of us.”

Malloy discussed efforts to address the state’s disparity in greater detail. Listen to his comments here:

Malloy said when cities like Bridgeport are graduating only about 65 percent of their students, “that is not a roadmap to recovery” or closing the economic gap. He said Connecticut’s educational reform package is designed to reduce the achievement gap between wealthy and the poor students. And the new Board of Regents for Higher Education, which brings together community colleges, state universities and an online college, is intended to help the state create a system that prepares more young people to be ready for the workforce.

Poverty in Conn. seen in lower high school graduation rates

Posted: August 15, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »Test scores released earlier this week by the Connecticut Department of Education highlighted, once again, a persistent gap between the performance of the state’s wealthiest students and the poorest ones. Now, the state has released information on a measurement that shows that achievement gap in even more stark terms – the percentage of students who graduate from high school in four years.

Listen to Craig LeMoult’s story about four-year graduation rates here:

The impact of income on graduation rates is evident in this map detailing the newly data, created for WSHU by the Connecticut State Data Center at the University of Connecticut. Click on the dots to see the graduation rate of individual high schools, and on the map to see the median family income of different census tracts they’re in. To see a full-screen version of the map, click here.

As you can see, the high schools with the lowest four-year graduation rates are clustered in the towns with the lowest median family income.

(Click here for the raw data by district, and here to see it by school).

In Connecticut during the 2012 academic year, the four year graduation rate for kids whose parents made too much money to qualify for help paying for lunch was 93 percent. For kids who got a reduced priced lunch, that graduation rate slipped to about 83 percent. And of the kids who were poor enough to be eligible for a free lunch, just around 66 percent of them graduated from high school in four years.

Robert Balfanz, the director of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, says if a student doesn’t graduate in four years, they’re likely to not graduate at all. He says although Connecticut is one of the wealthiest states, it under-performs its affluence.

“Its graduation rate is higher than the national average, but it’s not among the top,” says Balfanz. And I think that’s largely because the state overall is wealthy, but the wealth has significant unevenness in its distribution.”

Connecticut’s Commissioner of Education, Stefan Pryor, says the state is making an investment in the kinds of services he thinks will reduce the gap. “Just this year alone, in the new biennial budget the increase for Alliance Districts, the 30 lowest performing, highest poverty districts was increased by about 50 million dollars,” says Prior. “Another increase is budgeted for next year. On top of that, there are investments in family resource centers, school based health clinics, the Commissioner’s Network of individual low performing high poverty schools, and it goes from there.”

Pryor says he’s optimistic, because even though the new data show poverty continues to be correlated with lower graduation rates, there are also signs of improvement. For kids getting free lunches, the graduation rate is nearly six percent higher than last year. And for those getting reduced price lunch, it’s seven percent higher.

Conn. legislature considering minimum wage, retirement plan for low-income workers

Posted: May 8, 2013 Filed under: Education, General, Income, Politics Leave a comment »Connecticut’s legislative appropriations subcommittee approved two bills Tuesday related to economic disparity issues – one that would raise the minimum wage, and another that takes steps toward creating a state retirement plan for low income workers.

Hear about both bills here:

dk_bills_130508

The first bill would raise the minimum wage from $8.25 to $9 an hour over the next year and possibly to $9.75 the following year. Democratic State Representative Beth Bye of West Hartford says in the past she voted against raising the minimum wage. But now she says workers need it more than ever:

“What we’re seeing is this widening income disparity, in our state and in our country,” said Bye. “For people who are working full time I think we need to offer this as a way to help them to buy food and afford housing”

State Representative Mitch Bolinsky, a Newtown Republican, says the bill would prevent companies from hiring new employees, particularly teenagers. “The unemployment rate for that class of individual is three times higher than the state rate I see this as a job killing bill and a reason to have more kids on the street with nothing to do this summer,” said Bolinsky.

The bill is different from what Governor Dannel Malloy has proposed, which is to raise the minimum wage by 75 cents over the next two years. The committee bill still needs to be taken up by the House and Senate.

Also, the Appropriations Committee approved a bill that would require an initial feasibility study of a state administered retirement plan for low income workers. It made it through the committee on a mainly party line vote on Tuesday. Representative Jason Perillo of Shelton was one of a number of Republican members of the committee who voted against the bill. Perillo says there are plenty of private firms available to administer retirement plans for low income workers. The bill requires the Connecticut Retirement Security Trust Fund Board to set-up a low income workers fund, if the market feasibility study finds that such a fund would be self-sustaining. The bill heads to the Senate for further action.

A look inside one of Connecticut’s “failing” public schools

Posted: March 27, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »

Brookside Elementary teacher Keith Morey, diagramming how to write a CMT essay for his fifth graders

Listen to Craig LeMoult’s story about the school here:

lemoult_brookside_web_130326

Brookside’s not a wealthy school. 61% of kids at the school get free or reduced price lunch based on their family incomes. About 60% of the students in the school are Hispanic, and many of their parents don’t speak English. A lot of the kids don’t have any pre-schooling before they show up for kindergarten. A recent test showed that about 38% of kids walking in the Brookside Kindergarten door didn’t have the necessary basic skills – like knowing the alphabet and recognizing shapes.

As a result of the budget crunch, the school has lost it’s full-time literacy specialist and the library is closed every other week. But Brookside Principal David Hay says it’s not an excuse.

“That’s the first thing you’ve got to accept, that you can’t say ‘because we don’t have this, we won’t be able to do something with the children,” says Hay. “You got to recognize it, it’s not going to change. Income is probably the biggest thing, because kids don’t have experiences, resources, that a lot of the wealthier kids have. So we have to try to get those for them any way we can.”

Study: disparity in college attendance & graduation

Posted: March 22, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »A report in The Atlantic this week about a study by the think tank Third Way shows the income gap in college attendance and graduation rates. The following chart shows the percentage graduating college, based on what economic quartile they’re in. And it compares the oldest Millennial generation (red line) with the youngest Baby Boomers (dotted line).

Basically, according to the study, not only are poor students far less likely to go to college, they’re far more likely to drop out, leaving them with crippling debt.

For one Conn. school, early literacy is key to closing the achievement gap

Posted: March 15, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »

Principal Pamela Baim and Vice-Principal Dena Mortensen outside a third grade classroom at F.J. Kingsbury Elementary School in Waterbury

Here’s Will Stone’s story on Kingsbury Elementary School in Waterbury:

ws_kingsbury_130227

In 2011, the difference in reading between low-income fourth graders and their wealthier peers in the state was 35 points. And that same margin exists between white students and Hispanic and African-American students. But at Kingsbury Elementary, the picture is much different.

“Right now there is very small very small gap between the Hispanic white and black population,” says Principal Pamela Baim. “If you’re looking at every child and their need, the disparity should be very small, and that’s what we’re finding here.”

The school places students in tiers according to very specific criteria, such as oral fluency, and transition students to more challenging tiers as they show improvement. Teachers also spend hours training with the school’s team of reading specialists. They rely heavily on data and diagnostic tests, using a tiered system, and addressing literacy across the curriculum. And they say it’s helping closing the gap.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz: Inequality is holding back the recovery (Paul Krugman disagrees)

Posted: January 22, 2013 Filed under: Education, Employment, General, Income, Politics Leave a comment »The New York Times launched a new blog this week called The Great Divide, looking at inequality in the U.S. The blog is moderated by Joseph E. Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics, a Columbia professor and a former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers and chief economist for the World Bank. Stiglitz wrote the initial post in the blog, entitled “Inequality is holding back the recovery.”

“Politicians typically talk about rising inequality and the sluggish recovery as separate phenomena, when they are in fact intertwined,” Stiglitz writes. “Inequality stifles, restrains and holds back our growth.”

Stiglitz argues there are four major reasons inequality is squelching the recovery:

– The middle class is too weak to support the consumer spending necessary to drive growth

– The middle class is unable to invest in the future through education or starting/growing businesses

– The weak middle class holds back tax receipts needed for infrastructure, education, health, etc.

– Inequality leads to boom-and-bust cycles that make the economy more volatile and vulnerable

Stiglitz blames the economic policies of both the Obama and Bush administrations for making things worse.

“Instead of pouring money into the banks, we could have tried rebuilding the economy from the bottom up. We could have enabled homeowners who were ‘underwater’ — those who owe more money on their homes than the homes are worth — to get a fresh start, by writing down principal, in exchange for giving banks a share of the gains if and when home prices recovered. We could have recognized that when young people are jobless, their skills atrophy. We could have made sure that every young person was either in school, in a training program or on a job. Instead, we let youth unemployment rise to twice the national average. The children of the rich can stay in college or attend graduate school, without accumulating enormous debt, or take unpaid internships to beef up their résumés. Not so for those in the middle and bottom. We are sowing the seeds of ever more inequality in the coming years.”

He offers suggestions for President Obama’s second term.

“What’s needed is a comprehensive response that should include, at least, significant investments in education, a more progressive tax system and a tax on financial speculation.”

A lot to talk about here. Do you agree with Stiglitz’s arguments? Do you think inequality is holding us back from an economic recovery? What about his prescription for fixing it? Would education investment or a more progressive tax system make a difference?

Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman (also a Nobel laureate) disagrees with him. In two responses to Stiglitz (Jan. 20 & Jan. 21), he says he’d love to blame slow growth on inequality. “But I couldn’t and can’t convince myself that the theory and evidence really support that view,” he writes in the second piece. “Inequality is a huge problem – but not for employment growth in 2013 or 2014.”

Recent Comments