A look inside one of Connecticut’s “failing” public schools

Posted: March 27, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »

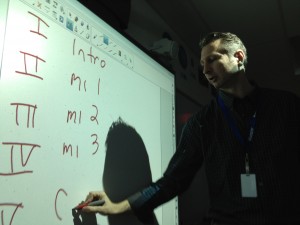

Brookside Elementary teacher Keith Morey, diagramming how to write a CMT essay for his fifth graders

Listen to Craig LeMoult’s story about the school here:

lemoult_brookside_web_130326

Brookside’s not a wealthy school. 61% of kids at the school get free or reduced price lunch based on their family incomes. About 60% of the students in the school are Hispanic, and many of their parents don’t speak English. A lot of the kids don’t have any pre-schooling before they show up for kindergarten. A recent test showed that about 38% of kids walking in the Brookside Kindergarten door didn’t have the necessary basic skills – like knowing the alphabet and recognizing shapes.

As a result of the budget crunch, the school has lost it’s full-time literacy specialist and the library is closed every other week. But Brookside Principal David Hay says it’s not an excuse.

“That’s the first thing you’ve got to accept, that you can’t say ‘because we don’t have this, we won’t be able to do something with the children,” says Hay. “You got to recognize it, it’s not going to change. Income is probably the biggest thing, because kids don’t have experiences, resources, that a lot of the wealthier kids have. So we have to try to get those for them any way we can.”

Study: disparity in college attendance & graduation

Posted: March 22, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »A report in The Atlantic this week about a study by the think tank Third Way shows the income gap in college attendance and graduation rates. The following chart shows the percentage graduating college, based on what economic quartile they’re in. And it compares the oldest Millennial generation (red line) with the youngest Baby Boomers (dotted line).

Basically, according to the study, not only are poor students far less likely to go to college, they’re far more likely to drop out, leaving them with crippling debt.

Brookings: income inequality sticking around

Posted: March 22, 2013 Filed under: General Leave a comment »A new study by the Brookings Institution says that the rise in inequality in the U.S. comes from significant changes in income over time. Co-author Bradley Heim told the Huffington Post, “it’s not that the rich will stay rich and the poor will stay poor, but that they are relatively less likely to switch positions than they were before.” HuffPo reports that according to the Economic Policy Institute, “the incomes of the top 1 percent of households spiked 241 percent between 1979 and 2007, while the incomes of the middle fifth grew just 19 percent, when adjusted for inflation.”

The Brookings study also suggests increasing federal taxes on the rich only modestly reduces inequality.

For one Conn. school, early literacy is key to closing the achievement gap

Posted: March 15, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »

Principal Pamela Baim and Vice-Principal Dena Mortensen outside a third grade classroom at F.J. Kingsbury Elementary School in Waterbury

Here’s Will Stone’s story on Kingsbury Elementary School in Waterbury:

ws_kingsbury_130227

In 2011, the difference in reading between low-income fourth graders and their wealthier peers in the state was 35 points. And that same margin exists between white students and Hispanic and African-American students. But at Kingsbury Elementary, the picture is much different.

“Right now there is very small very small gap between the Hispanic white and black population,” says Principal Pamela Baim. “If you’re looking at every child and their need, the disparity should be very small, and that’s what we’re finding here.”

The school places students in tiers according to very specific criteria, such as oral fluency, and transition students to more challenging tiers as they show improvement. Teachers also spend hours training with the school’s team of reading specialists. They rely heavily on data and diagnostic tests, using a tiered system, and addressing literacy across the curriculum. And they say it’s helping closing the gap.

Recent Comments