New Haven starts removing controversial fence between public housing and neighboring Hamden

Posted: May 13, 2014 Filed under: Housing, Income, Politics Leave a comment » New Haven began demolishing a fence on Monday that for 50 years separated a public housing complex in the city from the town of Hamden. For some, the fence had become a symbol of racial and economic division between two communities. The economic dividing line here is actually not one of the starkest in a state with one of the widest income disparities in the country. The most recent Census figures show median family income on the New Haven side was around $33,000, and it was about $70,000 on the Hamden side. But few places have anything as symbolically and literally divisive as the fence.Listen to Craig LeMoult’s story here:

Online tool to help find better Section 8 housing wins contest

Posted: April 30, 2014 Filed under: Housing Leave a comment »

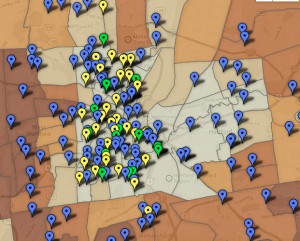

An online map will show people looking for Section 8 housing where community resources are. It’s at http://ctoca.org/map/

“What we did today was we tried to create a mapping tool, where we would have a system where the clients and the counselors could sit together, enter the address and get information about neighborhood assets,” said Boggs.

Those neighborhood assets include things like schools and grocery stores, and the tool also has community information like unemployment rates and crime statistics. Boggs says that kind of information can help families move to communities where they can be more successful. She says currently, nearly 80 percent of Section 8 vouchers are disproportionately used in high poverty areas.

For now, the tool focuses on the Hartford area. An award of $1,000 in Tuesday’s contest will help them extend it to cover the entire state.

City mayors describe inequality with suburbs

Posted: April 30, 2014 Filed under: Housing, Income, Politics Leave a comment »

(L to R) Former New Haven Mayor John DeStefano, Norwich Mayor Deb Hinchey, Harford Mayor Pedro Segarra

Hartford Mayor Pedro Segarra said for the most part, Connecticut is a liberal state.

“I just think that when it comes to protecting people’s wallets, we’re a lot more conservative.”

Segarra said the fiscally conservative suburban towns aren’t willing to step in to help the state’s larger cities. Former New Haven mayor John DeStefano said Connecticut’s three biggest cities have nearly three quarters of the state’s affordable housing stock.

“The choices made 100 years ago and the choices that many of the communities of CT continue to make about who they zone out, has resulted in a separating of populations and concentrations of poverty and wealth in the state.”

That poverty is also concentrated in some of Connecticut’s smaller cities, like Norwich. Norwich Mayor Deb Hinchey, said the cities all wind up fighting for a finite amount of money.

“And where I become concerned about the inequalities is where that finite group of dollars isn’t disbursed evenly throughout the state.”

Hinchey said the state needs to reform its tax laws to be more fair. DeStefano, who retired last year after 10 terms in office, laughed at that, and said he could tell she’s new to the job.

DeStefano said cities in Connecticut need to take action to reduce their own economic inequality, rather than waiting for the state to take steps. Segarra challenged DeStefano on that, suggesting Hartford has a harder time making changes to impact the economic health of the city. Here’s their exchange.

Segarra said his administration is working on building housing to attract those higher-income people to live in Hartford. In New Haven, DeStefano provided incentives for Yale University employees to live in the city. Yale is the city’s largest employer, and provides more than $15 million a year in payments to support city services.

Conn. NAACP describes “urban Apartheid”

Posted: April 10, 2013 Filed under: Employment, General, Housing, Income Leave a comment »NAACP members in greater New Haven are calling on the federal and state government to re-examine the disparities between low-income people of color in urban neighborhoods and white people in the suburbs. The report, called “Urban Apartheid,” looks at disparities in areas like education, income, and housing.

You can hear Will Stone’s story on the report here:

ws_naacp_130329

NAACP Chapter President James Rawlings says the findings show that place matters. He means neighborhoods in and around New Haven where, for example, the poor are six times less likely to have access to transportation, which in turn affects their chances of employment. A quarter of African American men in the region were unemployed in 2011. Rawlings says it all comes back to the educational achievement gap, and he says the key is removing children from what he calls “unhealthy communities.”

“The transportation system isn’t there to support the children, libraries are not there to support the child, the family wrap-around services are not there to support the child,” he says.

The NAACP is recommending that affordable housing be placed in more suburban communities, where the air is cleaner and there’s less crime.

Report: Conn. among worst for home ownership, credit card debt

Posted: January 30, 2013 Filed under: General, Housing Leave a comment »A new report from an economic advocacy group ranks Connecticut among the worst states for affordable home ownership and credit card debt, and it raises some interesting economic disparity issues about the state. Listen to the story here:

cel_cfed_130130

The national study from the DC-based Center for Enterprise Development found that in Connecticut, 37% of households don’t have enough money to cover basic expenses for three months if they lose their income.

“What I think is surprising is how far up the income scale liquid asset poverty reaches,” says Jennifer Brooks, director of state and local policy at CFED. She says 15% of Connecticut households that earn between $65K and $107K a year don’t have three months worth of savings.

Where Connecticut really stands out in the report is home ownership. The state ranks 42nd on the study’s measure of home affordability, which compares household income to median housing value. And the report says 41% of households in CT are paying more than a third of income for mortgage & other housing costs. And more than half of renters are using up that much of their income on housing. Brooks says there’s a huge disparity in home ownership based on income. She acknowledges it’s not surprising that high income families are more likely to own homes than low income families.

“I think that fact that Connecticut ranks 46th on this disparity measure is important, so the gap in CT is much bigger than it is in many other states,” she says.

The report shows there are also home ownership disparities based on race and family structure. It also says the average credit card debt in Connecticut is $15,000, second only to Washington DC.

CFED recommends a dozen policy recommendations in its report, including suggestions on how to reduce credit card debt and improve homeownership rates.

Report: Affordable housing limited in more than half of Conn. towns

Posted: November 19, 2012 Filed under: Housing Leave a comment »

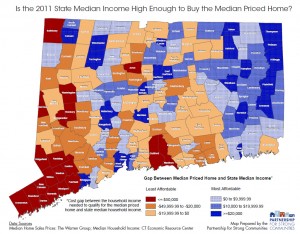

This map, from the Partnership for Strong Communities, illustrates the gap between the state median income, and the income needed to qualify for a mortgage to buy a house at the median price in that city or town (click to make the map bigger)

A new report from the advocacy group Partnership for Strong Communities says Connecticut’s median income in 2011 ($70,705) wasn’t enough to qualify for a mortgage in just over half of the state’s cities and towns (based on the median price in that town). You can hear about the study here:

DK_realestatereport_121114

According to the story, the three least affordable towns — Greenwich, New Canaan and Darien — had median home sale prices over $1 million. Those towns all had median household incomes over $120,000. As we’ve previously reported, Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy has made a commitment to improve access to affordable housing in the state.

Dealing with blighted homes in CT’s poorer cities

Posted: November 19, 2012 Filed under: Housing Leave a comment »

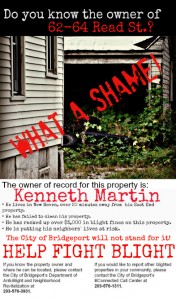

It’s probably not a big surprise that Connecticut’s less wealthy cities have a greater problem with blighted homes than some other communities. But Bridgeport Mayor Bill Finch made a point of raising the economic issues in this story about a new plan to shame owners of falling-apart homes.

Finch says dealing with houses like this is particularly a problem in low income areas like Bridgeport because property values are lower.

“So people sort of just write their property off and abandon them,” he says. “And we’re left to clean up the legal mess and the mess of the facility itself.”

And he says the courts are stacked against cities in disputes over these abandoned properties.

“The court system is knee deep in rules and regulations that protect private property and very very difficult for cities and towns to go after people who are not taking care of their property.”

Conn. invests in affordable housing in “Gold Coast”

Posted: August 30, 2012 Filed under: Housing Leave a comment »

Lisa Joyner-Kendall washes dishes in her public housing home in Stamford. Joyner-Kendall hopes to soon be able to afford to buy her own home.

A commitment by Connecticut to spend $500 million on affordable housing over the next 10 years might help an affordable housing crunch on the the state’s Gold Coast. Darien has a median home price of more than $1 million, making affordable housing hard to come by. WSHU’s Kaomi Goetz reports a recent groundbreaking at a development in Darien underscores both the need and the difficulty of creating new units. Listen here:

The 106 rental units and new community center called ‘The Heights of Darien’ are being built with nearly $30 million dollars in federal and state tax credits. The town is also kicking in local support.

How fair are property taxes?

Posted: July 17, 2012 Filed under: Housing Leave a comment »

Karen Smith (above) is going through foreclosure on her grandmother’s Bridgeport home because of their failure to pay property taxes. As part of the foreclosure, the city had an appraisal of the property done. It said the house is worth $35,000. But for property taxes, the house is assessed at $121,590. So why the difference? Is the property over-assessed? Or is the assessment too low?

Both may be the case. Property tax revaluations only happen every five years in Connecticut, and the assessment on Smith’s house is based on 2007 values, before the housing crash. And the appraisal is based on comparable properties nearby, all of which are foreclosure sales.

In June, Governor Malloy vetoed a bill that would have allowed five cities and towns to postpone their property tax revaluations. You can hear our discussion of that, Karen Smith’s story, and the overall fairness of property tax assessments here:

lemoult_assessments_120607

Smith said her neighbors’ properties were over-assessed, too, and we wanted to see if that was true. So we plotted more than 40,000 properties on a map that had sold in recent years, and color-coded them to see where there was a significant difference between the assessed value and the sale price. Homes that are assessed at at least double what they sold for are red. In Smith’s neighborhood, the East End of Bridgeport, there was a significant cluster of red.

Zoom out to see the rest of the state. There are similar clusters of red in cities like Waterbury and New Haven. The main explanation for that is that most of those “red” properties are foreclosure sales or some other kind of bank sale. Basically, if you live in a neighborhood that was clobbered by the housing crisis, you’re probably still paying property taxes on a value that your home is no longer worth. In the wealthier areas, houses mostly sold for more than their assessed value.

New Haven tries mixing things up in public housing

Posted: February 23, 2012 Filed under: Housing Leave a comment »New Haven is holding a lottery. The jackpot: the opportunity to live in a brand new public housing community. You can hear our story about it here:

For city residents like Richard Estrada, winning would mean a lot. He’s got two boys at home, one of whom has autism and who he says needs more space than he’s got now. Estrada’s not your usual public housing tenant. He’s got a good job, running maintenance for the city’s police stations. But that’s the idea of this lottery: the city’s looking for the working poor. The idea is to get people with different incomes living together. The federal government funds hundreds of mixed income communities like this around the country. New Haven is using some money for this development that would have otherwise supported housing vouchers. People can use vouchers to help pay rent at apartments around the city. Bob Ellickson, who teaches property law at Yale, says these mixed income communities are way better than the old model of clustering the poorest people in massive projects. But he says they’re not as good as the vouchers, which he says help twice as many people. Federal housing officials say rent vouchers can only do so much. This project is a brand new development with built-in social services, like job training. Add in the lottery to mix things up economically, and, they say, you may have created a community that can make some progress against poverty.

Recent Comments