Malloy discusses disparity and workforce training with National Governor’s Association

Posted: October 22, 2013 Filed under: Education, Income Leave a comment » At a summit of the National Governor’s Association in Stamford on Tuesday, Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy spoke with Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin and others about the economic importance of education and workforce training. You can listen to Craig LeMoult’s report here.Governor Fallin said 50 years ago, 80 percent of middle class jobs in the country required just a high school degree or less. “Today that number is 35 percent of our jobs require a high school degree or less, and two thirds of those jobs will pay less than $25,000 a year,” said Fallon.

Malloy said there’s no reason to believe Connecticut is not leading the country in the decline in the number of jobs available to people without a higher education degree. “And then, in some of our urban areas, we have a larger than we should find acceptable numbers of students that don’t even get the high school degree, at least in the standard 13 years,” said Malloy. “So this is a big questions for all of us.”

Malloy discussed efforts to address the state’s disparity in greater detail. Listen to his comments here:

Malloy said when cities like Bridgeport are graduating only about 65 percent of their students, “that is not a roadmap to recovery” or closing the economic gap. He said Connecticut’s educational reform package is designed to reduce the achievement gap between wealthy and the poor students. And the new Board of Regents for Higher Education, which brings together community colleges, state universities and an online college, is intended to help the state create a system that prepares more young people to be ready for the workforce.

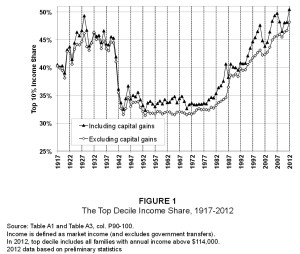

Wealthiest having much easier time bouncing back from recession

Posted: September 12, 2013 Filed under: General, Income, Politics Leave a comment »A new study by Emmanuel Saez at U.C. Berkeley says that the economic recovery has been far more generous to the wealthiest Americans than to the rest of the country. From 2009-2012, according to the study, incomes of the top 1% of Americans grew by 31.4% while the incomes of the other 99% grew just 0.4%. This chart from study shows what percentage of the total income share was held by the top 10% (decile) from 1917-2012.

Source: “Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States” by Emmanuel Saez, UC Berkeley

As you can see, there was a serious drop-off around the time of World War II, and the levels stayed fairly constant between 30-35% until the late 1970s. They’ve now climbed back up to an all-time high.

The study was a topic of discussion today on the Diane Rehm Show on NPR. You can listen to that conversation here.

Stephanie Coontz of the Council on Contemporary Families said on the show that this is a long-term change.

“I think it’s a mistake to just think of it in terms of the recession,” she said. “It’s actually a 30 year process that has turned around all of the trends we had after the Great Depression and the move toward greater equality, and greater sense of community among the rich as well as the poor. I think the social implications of this are profound at all levels of society.”

Wall Street Journal columnist Dante Chinni, who directs the American Communities Project at American University discussed the causes of the growing disparity.

“You have the decline of good paying jobs, of manufacturing jobs,” he said. “And they were hard jobs, but they paid well. And they’ve disappeared. And that’s made life very hard. Also, automation. There are just fewer jobs available for people who don’t have a lot of education, and a lot of good skills training.”

The show’s other guest Columbia University journalism professor Thomas Edsall recently wrote a blog post for the New York Times on whether the government can actually do anything about inequality. On a somewhat related note, economist Steven Lanza looked at the issue of what difference government policies can make on the economy in Connecticut. His answer: not much. A WSHU story on his paper is here.

Also today, NPR Morning Edition’s Steve Inskeep spoke with Tyler Cowan, author of the book “Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation.” Cowan predicts the future means more people rising up to much greater wealth, as well as more clustering in a kind of “lower-middle class existence.”

“It will be a very strange world, I think,” he said. “We will be returning to historical levels of inequality. We’ll view post-war America as a kind of strange interlude not to be repeated. It won’t be the dreams that we all had that virtually all incomes go up in lockstep at three percent a year. It hurts to give that up. It will mean some very real increases in economic fragility for a lot of people.”

You can listen to Cowan’s conversation with Inskeep here.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments, email disparity@wshu.org or tweet us at @CTdisparity.

Poverty in Conn. seen in lower high school graduation rates

Posted: August 15, 2013 Filed under: Education Leave a comment »Test scores released earlier this week by the Connecticut Department of Education highlighted, once again, a persistent gap between the performance of the state’s wealthiest students and the poorest ones. Now, the state has released information on a measurement that shows that achievement gap in even more stark terms – the percentage of students who graduate from high school in four years.

Listen to Craig LeMoult’s story about four-year graduation rates here:

The impact of income on graduation rates is evident in this map detailing the newly data, created for WSHU by the Connecticut State Data Center at the University of Connecticut. Click on the dots to see the graduation rate of individual high schools, and on the map to see the median family income of different census tracts they’re in. To see a full-screen version of the map, click here.

As you can see, the high schools with the lowest four-year graduation rates are clustered in the towns with the lowest median family income.

(Click here for the raw data by district, and here to see it by school).

In Connecticut during the 2012 academic year, the four year graduation rate for kids whose parents made too much money to qualify for help paying for lunch was 93 percent. For kids who got a reduced priced lunch, that graduation rate slipped to about 83 percent. And of the kids who were poor enough to be eligible for a free lunch, just around 66 percent of them graduated from high school in four years.

Robert Balfanz, the director of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, says if a student doesn’t graduate in four years, they’re likely to not graduate at all. He says although Connecticut is one of the wealthiest states, it under-performs its affluence.

“Its graduation rate is higher than the national average, but it’s not among the top,” says Balfanz. And I think that’s largely because the state overall is wealthy, but the wealth has significant unevenness in its distribution.”

Connecticut’s Commissioner of Education, Stefan Pryor, says the state is making an investment in the kinds of services he thinks will reduce the gap. “Just this year alone, in the new biennial budget the increase for Alliance Districts, the 30 lowest performing, highest poverty districts was increased by about 50 million dollars,” says Prior. “Another increase is budgeted for next year. On top of that, there are investments in family resource centers, school based health clinics, the Commissioner’s Network of individual low performing high poverty schools, and it goes from there.”

Pryor says he’s optimistic, because even though the new data show poverty continues to be correlated with lower graduation rates, there are also signs of improvement. For kids getting free lunches, the graduation rate is nearly six percent higher than last year. And for those getting reduced price lunch, it’s seven percent higher.

Trying to reach the bottom rung of the economic ladder

Posted: July 25, 2013 Filed under: Employment, Income Leave a comment »

Rodney Moore of New Haven Family Alliance, speaking with participants in the Project Success program

A report out this week by researchers at Harvard and U.C. Berkeley found the chance that someone born into the bottom fifth of the economic ladder in Connecticut could rise to the top fifth is about 8%. For some young low-income people, even the bottom rung of that economic ladder feels out of reach. One program in New Haven is working to help them start that climb.

Listen to Craig LeMoult’s story here:

lemoult_projectsuccess_130724_web

The New Haven Family Alliance runs a program called Project Success to help young people who don’t see a path for themselves to jobs in the regular economy. Economists say even with a regular job, climbing out of poverty is a challenge.

Despite disparity, Conn. not the hardest place to move up economic ladder

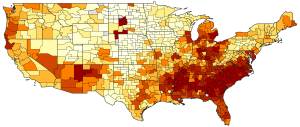

Posted: July 25, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »A report out this week by researchers at Harvard and U.C. Berkeley examines the ability of people to move up the economic ladder in metro areas around the country. They found striking differences in upward mobility based on where in the country people live. This map from the study illustrates the regional differences. The red spots are where it’s hardest to move up, and the lighter areas are where that kind of mobility is easier.

There’s a New York Times interactive map and article on the study here.

Interestingly, although Connecticut has one of the greatest economic disparities in the country, as you can see on that map, it’s not one of the hardest places to move up the economic ladder. The study found that in the Bridgeport area (the one area of Connecticut included in the study) the chance that someone in the bottom fifth of the economic ladder could rise to the top fifth is about eight percent. Compare that to Atlanta, which is just four percent. The study says Bridgeport kids who grow up in the first percentile in income, just $2,000 a year, will end up, on average, in the 35th percentile.

Coming up shortly on WSHU’s State of Disparity, we’ll take a look at efforts to help young people who are having trouble even reaching the bottom rung of the economic ladder.

NY Times: “No rich child left behind”

Posted: May 8, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »In a commentary on the New York Times’ fascinating online series on inequality, “The Great Divide,” Stanford professor Sean Reardon argues that much of the educational achievement gap in the U.S. comes not simply from a difference between the quality of rich and poor schools. He says the biggest difference is how much rich families are spending on the academic development of their kids.

Reardon says test scores for the poorest students aren’t dropping. Test scores for the richest students have risen dramatically. “Before 1980,” he writes, “affluent students had little advantage over middle-class students in academic performance; most of the socioeconomic disparity in academics was between the middle class and the poor. But the rich now outperform the middle class by as much as the middle class outperform the poor.”

He says it boils down to this: “The academic gap is widening because rich students are increasingly entering kindergarten much better prepared to succeed in school than middle-class students. This difference in preparation persists through elementary and high school.”

And he says it’s not just that the rich have more money than they used to. It’s how they use it:

“High-income families are increasingly focusing their resources — their money, time and knowledge of what it takes to be successful in school — on their children’s cognitive development and educational success. They are doing this because educational success is much more important than it used to be, even for the rich.”

In several earlier stories, we’ve focused on arguments educators are making on what schools can do to close the achievement gap, like this story on early childhood literacy, this one on Brookside Elementary School in Norwalk and this one on half-day kindergarten. Reardon argues here that “improving the quality of our parenting and of four children’s earliest environments may be even more important.” And he points to programs and policies like maternity and paternity leave that he says could lead to that goal.

Read Reardon’s full story here.

Conn. legislature considering minimum wage, retirement plan for low-income workers

Posted: May 8, 2013 Filed under: Education, General, Income, Politics Leave a comment »Connecticut’s legislative appropriations subcommittee approved two bills Tuesday related to economic disparity issues – one that would raise the minimum wage, and another that takes steps toward creating a state retirement plan for low income workers.

Hear about both bills here:

dk_bills_130508

The first bill would raise the minimum wage from $8.25 to $9 an hour over the next year and possibly to $9.75 the following year. Democratic State Representative Beth Bye of West Hartford says in the past she voted against raising the minimum wage. But now she says workers need it more than ever:

“What we’re seeing is this widening income disparity, in our state and in our country,” said Bye. “For people who are working full time I think we need to offer this as a way to help them to buy food and afford housing”

State Representative Mitch Bolinsky, a Newtown Republican, says the bill would prevent companies from hiring new employees, particularly teenagers. “The unemployment rate for that class of individual is three times higher than the state rate I see this as a job killing bill and a reason to have more kids on the street with nothing to do this summer,” said Bolinsky.

The bill is different from what Governor Dannel Malloy has proposed, which is to raise the minimum wage by 75 cents over the next two years. The committee bill still needs to be taken up by the House and Senate.

Also, the Appropriations Committee approved a bill that would require an initial feasibility study of a state administered retirement plan for low income workers. It made it through the committee on a mainly party line vote on Tuesday. Representative Jason Perillo of Shelton was one of a number of Republican members of the committee who voted against the bill. Perillo says there are plenty of private firms available to administer retirement plans for low income workers. The bill requires the Connecticut Retirement Security Trust Fund Board to set-up a low income workers fund, if the market feasibility study finds that such a fund would be self-sustaining. The bill heads to the Senate for further action.

Greenwich, as a model of equality in schools

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a comment »In a recent article in the New York Times, Adam Davidson the creator of NPR and This American Life’s “Planet Money” podcast and blog, described the economic diversity in Greenwich. While the town is mostly known for it’s remarkable wealth, it also has a sizable population of working class people. Nearly 4 percent live below the federal poverty line. Although it’s a town with expensive housing, the draw for many is the schools. And, Davidson writes, studies have shown that low income students ido better in wealthy schools than in poor ones. He writes about Greenwich High School:

“Around 13 percent of the school’s students receive free or discounted lunches, a commonly used proxy for low income. And more than three-quarters of those students scored at or above proficiency on the most recent statewide 10th-grade performance tests. At nearby Stamford High School, where nearly 70 percent of students are on the lunch program, almost half the students failed to meet proficiency levels.”

Davidson spoke with Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, who says about 10 percent of all students in the country are in districts that have some kind of economic-integration policy.

“The remarkable thing about economic integration, Kahlenberg says, is that it seems to improve outcomes for the poor without diminishing educational attainment among the rich. Christopher Winters, headmaster of Greenwich High School, says that the greater diversity of the population makes for a better educational experience for all students. The low-income population has nearly doubled in the past seven years at Greenwich High, and no parent, he said, has complained.”

You can read Davidson’s full article here. And here’s our earlier coverage of an effort to create a mixed income community in New Haven.

Food insecurity a complicated problem in Conn.

Posted: April 10, 2013 Filed under: General, Health, Income, Nutrition Leave a comment »

Katherine Sebastian-Dring who work at the Gemma E. Moran United Way Labor/Food Center stands on the left, next to Bob Davoy who runs a food pantry in downtown New London. Mary Gates (right) is an Americorp VISTA for the New London Food Policy Council.

Recently a national anti-hunger advocacy group ranked Connecticut as the 6th best state for access to affordable and nutritious food—what’s also called community food security. But a study released Wednesday by UConn’s Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy shows that things are pretty tough in some areas.

You can hear Will Stone’s report on food insecurity here:

ws_foodsecurity_130409

1 in 6 children in New London County is food insecure. That means they and their families don’t have reliable access to affordable food for a number of reasons—transportation, education, geography and income, all play a role.

It’s not all about economic disparity for this issue. The per capita income in the city of New London is $21,000, while neighboring Stonington is almost twice that. But the report shows Stonington still has a higher than average risk of food insecurity.

“Every town in the county has an at-risk population,” says Mary Gates, who’s been conducting focus groups on food insecurity for the New London Food Policy Council. “I want to make sure that people don’t look at Stonington or Mystic and say there can’t be hungry people there.”

Conn. NAACP describes “urban Apartheid”

Posted: April 10, 2013 Filed under: Employment, General, Housing, Income Leave a comment »NAACP members in greater New Haven are calling on the federal and state government to re-examine the disparities between low-income people of color in urban neighborhoods and white people in the suburbs. The report, called “Urban Apartheid,” looks at disparities in areas like education, income, and housing.

You can hear Will Stone’s story on the report here:

ws_naacp_130329

NAACP Chapter President James Rawlings says the findings show that place matters. He means neighborhoods in and around New Haven where, for example, the poor are six times less likely to have access to transportation, which in turn affects their chances of employment. A quarter of African American men in the region were unemployed in 2011. Rawlings says it all comes back to the educational achievement gap, and he says the key is removing children from what he calls “unhealthy communities.”

“The transportation system isn’t there to support the children, libraries are not there to support the child, the family wrap-around services are not there to support the child,” he says.

The NAACP is recommending that affordable housing be placed in more suburban communities, where the air is cleaner and there’s less crime.

Recent Comments